A TRANSLATED TOUR

A multilingual resource to improve your experience in the Ter Museum.

Mobile devices are available for our visitors.

01

The River Factory

Can Sanglas

In 1841, after the destruction caused by the Carlist assault on Manlleu, the businessman Martí Sanglas Pradell acquired the water rights to set up a cotton mill, which is the factory that can still be seen today. This event marked the birth of modern industry in Manlleu, and in the Ter river basin as a whole.

From Factory to Museum: 150 years working as an Industrial Building

02

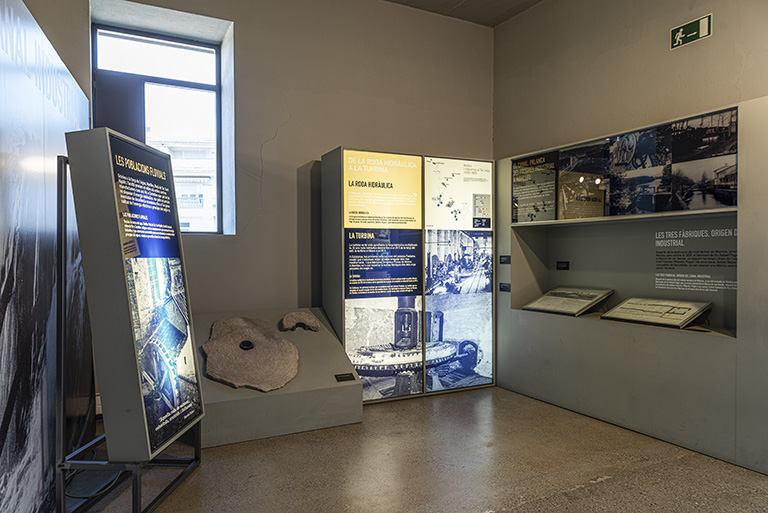

From a Watercourse to an Industrial Canal

The benefits offered by the use of hydraulic energy led to the construction of several factories along the banks of the River Ter. As early as 1829, the old watercourse of the Dalt mill in Manlleu was used to power a cotton mill. From 1841 onwards, the growing demand in the industrial use of water led to the transformation of the watercourse into the first industrial canal in Catalunya.

03

The River Towns

Thanks to water power, Manlleu, Roda de Ter, Sant Hipòlit and Torelló took over from the former manufacturing centres of Vic and Centelles, which all lacked access to hydraulic power. The local economies of the latter towns fell into an inevitable decline, until the early twentieth century, when the use of electricity became widespread.

04

From Water Wheels to Turbines

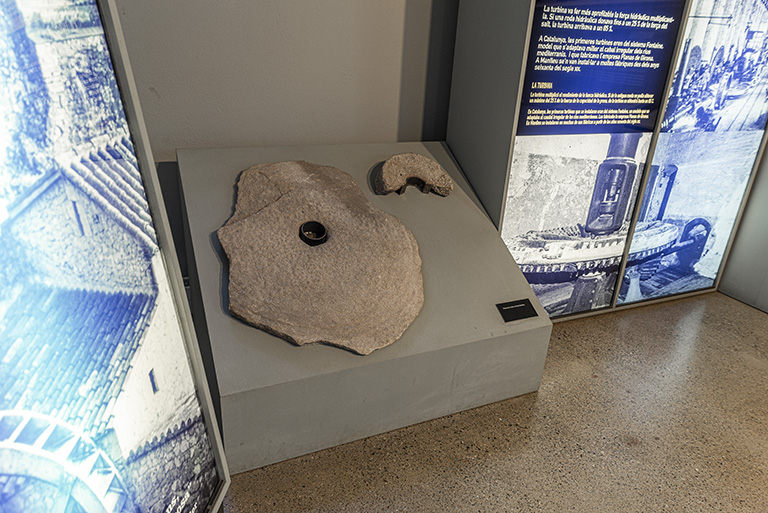

Water Wheels

Water wheels have been used throughout history to convert the force of flowing water into mechanical energy. In this region the process was used to power mills for wheat, grain, oil and paper, as well as fulling machines, forges and pre-industrial saw mills.

Turbines

The introduction of turbines increased the effectiveness of hydraulic energy. While traditional water wheels were able to obtain a maximum of 25% yield of a dam's energy capacity, while turbines delivered up to 85% of its potential. The first turbines to be installed in Catalonia were Fontaine system devices, a model well-suited to the irregular flow of Mediterranean rivers. They were manufactured by the Planas Company of Girona and were installed in many factories in Manlleu from the 1860s onwards.

05

The Canal, the Driving Force of Industrial Progress in Manlleu

The industrial canal allowed for the intensive use of hydraulic energy. It was further developed in a series of alterations and extensions, and by 1848 it was supplying seven textile mills.

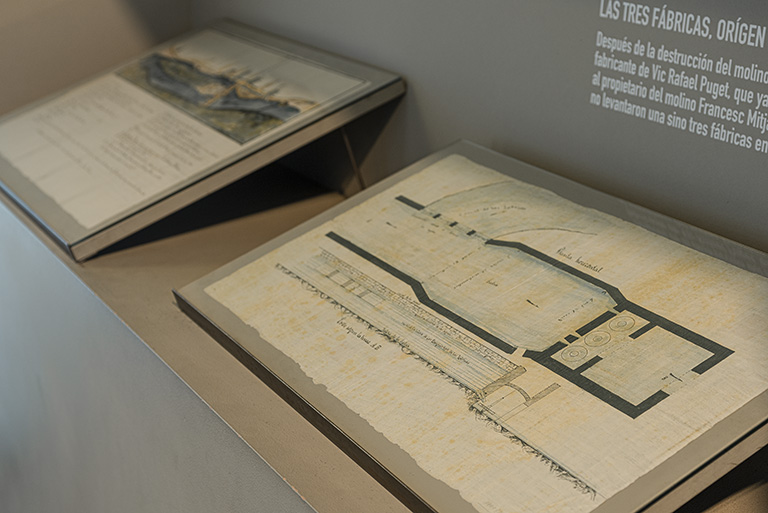

The Three Factories, the Origin of the Industrial Canal

The Miarons flour mill was destroyed when Carlist militia forces burnt down Manlleu in 1839. A manufacturer from Vic, Rafael Puget, who already ran the Can Barola factory, acquired the land and the water rights from the mill’s owner, Francesc Mitjavila. Puget and his business partners, Antoni Baixeras from Vic and Salvador Juncadella from Barcelona, built not one, but three factories along the final section of the Carrer de Vendrell.

06

Alternators

The introduction of dynamos on the rotating axis of turbine mechanisms meant that they could be used to generate electrical current. From the dawn of the new century, water once again began to challenge coal, but this time as a source of electricity.

07

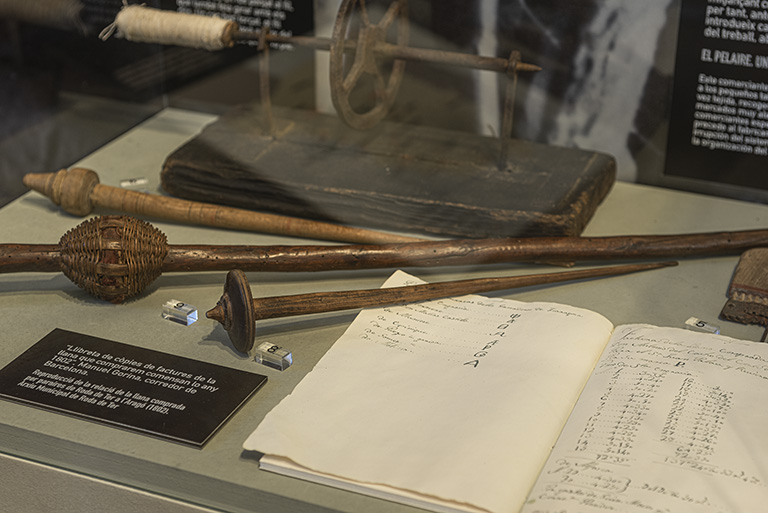

Before the Factory

Manufacturing has long been a traditional activity in Catalonia. Wool, linen and hemp have all been used as basic textile products since ancient times. Together with the guilds in the towns and cities, a widespread rural cottage industry sprang up during the 18th century in the hinterland of the Catalonia, in places such as Osona; this economic structure was controlled by the wool factors and their dealers.

08

The Wool Factor. A Factor without a Factory

The “pelaire”, or “wool factor”, was a dealer who delivered wool to small workshops and cottage workers, and then collected it once it had been woven. He would often sell the cloth in markets a considerable distance away, operating through a network of specialist dealers. These wool factors pre-date the cotton manufacturers, and they brought about major changes in the way labour was organised, long before the factory system emerged.

09

Home-spinning

Until the end of the 18th century, home spinning represented a major supplementary income for many rural families in the region. Spinning was a task that was generally performed by women before the appearance of the first manual machines.

10

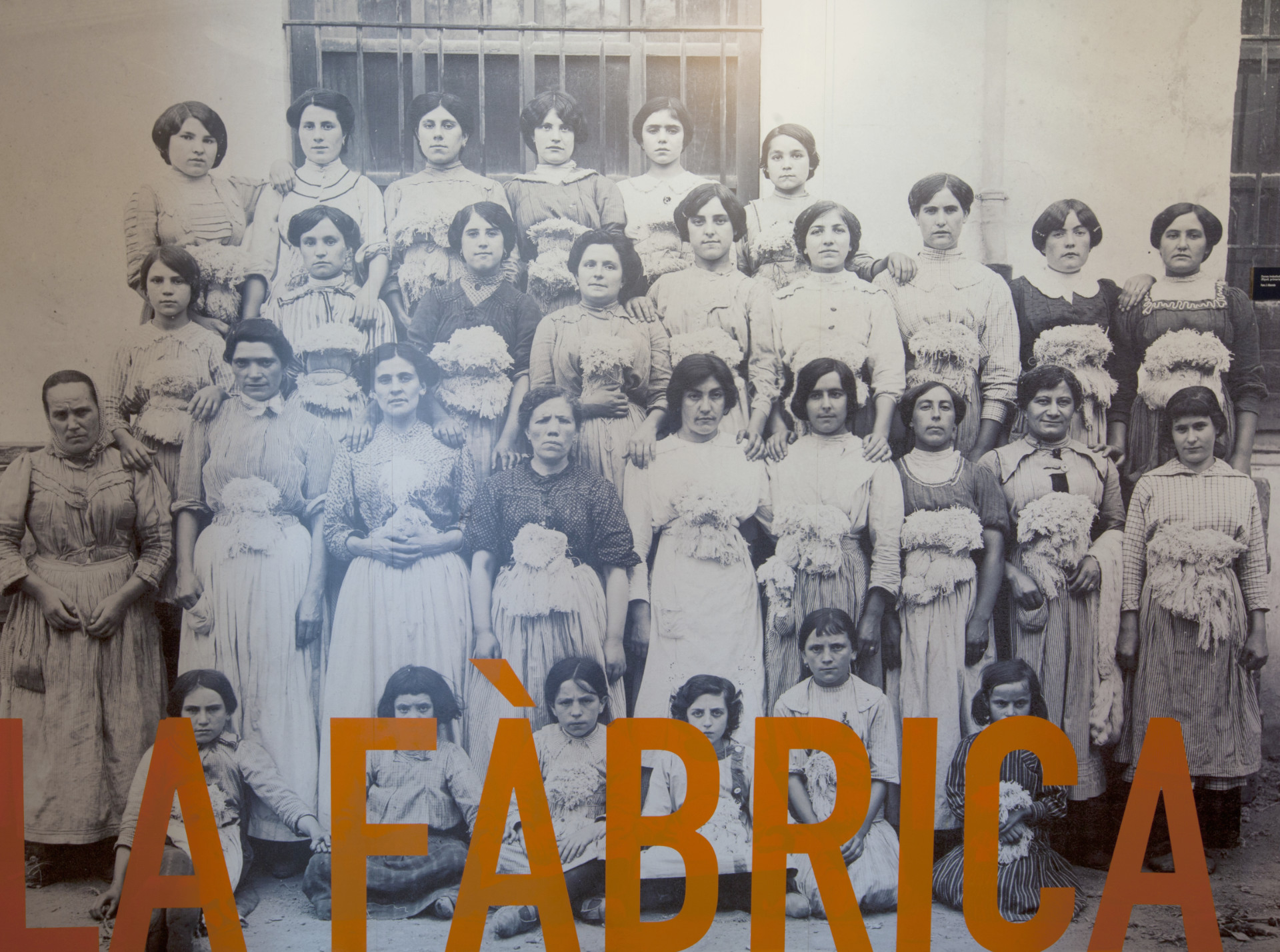

The Factory

Factories, i.e. buildings where manufacturing processes take place did not appear on the Ter until the early 19th century. It was then that modern businessmen replaced the old wool factors, and at precisely the moment when the need for greater investment capital became apparent. In 1802 there were already three cotton mills in Manlleu that used wooden, manual machinery. By 1816, the number had risen to six.

The concentration of the labour force in factories allowed manufacturers to reduce both wages and transport costs, while also leading to increased productivity, thanks to the use of machinery that would later be operated by hydraulic power. At sometime around 1860, riverside factories along the Llobregat and Ter rivers became the prime movers in the industrialisation of Catalunya.

11

Peasants and Craftsmen transformed into Workers

The new factory system brought about a decline in the workers’ living conditions, a fact that would last for decades. Production lines and specialisation strategies removed the workers’ ability to retain their economic independence, converting them into nothing more than wage slaves. Long, tough working days were to transform even the concept of time itself, which now moved at the pace of this new productive discipline.

12

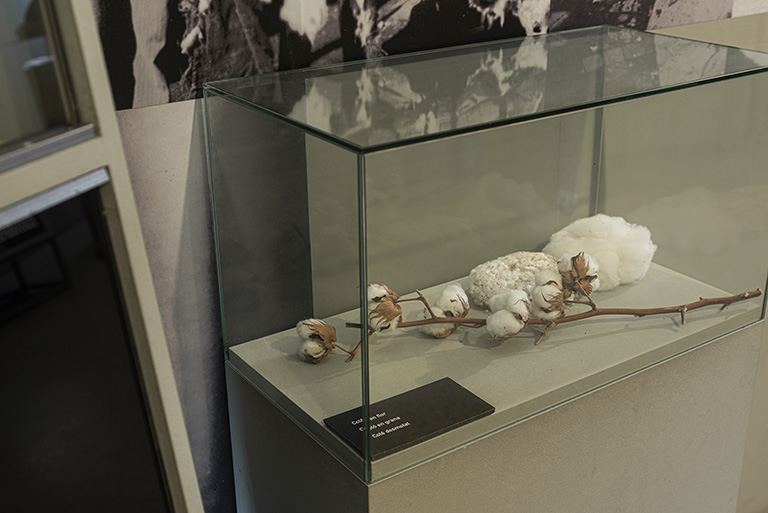

King Cotton

Cotton soon swept aside all other textile fibres that had previously been used in clothing. The advantages it offered were obvious: it was easier to work and dye, the low cost of raw materials, together with its excellent hygiene and sanitary properties - it maintained body temperature and it was breathable. All this meant that the mechanisation of cotton production, which culminated in the mid-nineteenth century, came about before that of wool.

13

A Fibre from Afar

The cotton plant is native to sub-tropical climes. In the 18th century, printed cotton fabrics came from the Near East or India. From 1790, when cotton spinning began in Catalonia, the majority of raw cotton used was imported from both the southern states of the United States and Egypt.

14

The Unstoppable Machine

Mechanisation – the Transformation of the Global Economy a Spectacular Increase in Manufacturing Capacity

The key element in any factory is the concentration of machines and workers. These new manufacturing spaces were to produce an authentic revolution in terms of productivity. Firstly through the use of manual machines based on the English jenny, such as the bergadana. Later, hydraulic energy was used, with the water frame, and types of spinning machines that were known as mule-jennys and self-acting mules. Men and women shared manufacturing tasks, although women were paid far lower wages.

15

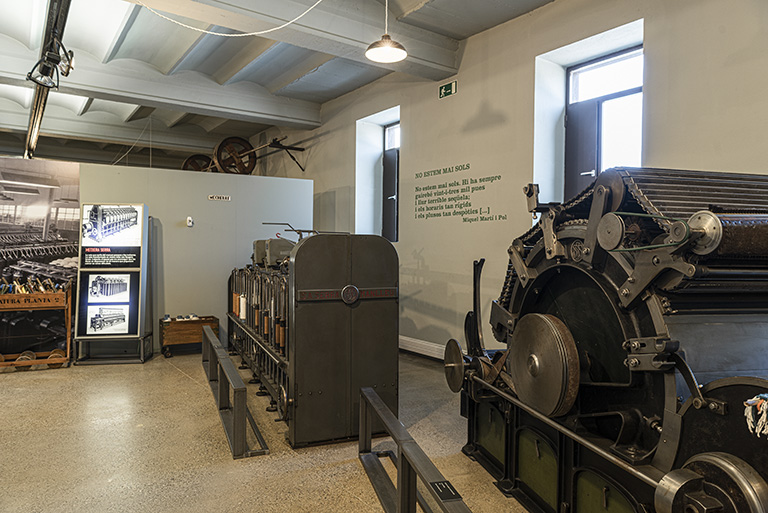

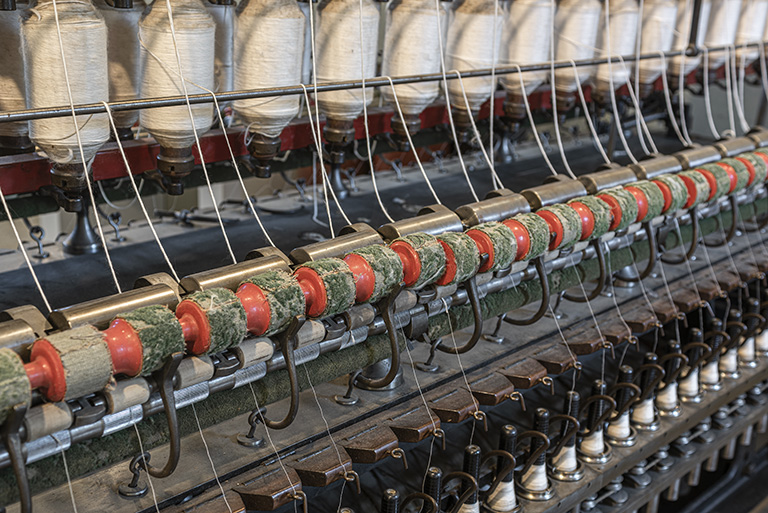

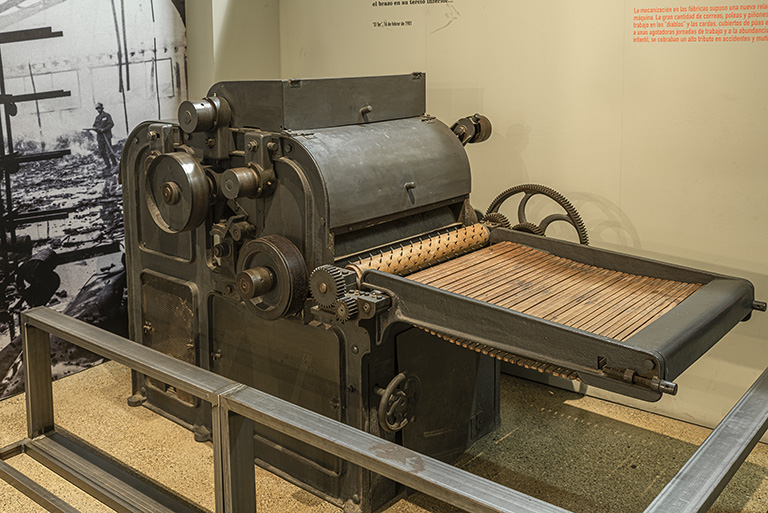

The Serra Carding Machine

The twisted cotton strands were disentangled through the use of drums and carding paddles. Compressing the fleece or lappe produced a ribbon shape to the loose strands of fibres (known as the silver) as they were passed through two production rollers before going on to the drawing and the roving frames.

16

The Serra Drawing Frame

The loose yarn that emerged from the drawing frame then went on to the roving frames. This ribbon-shaped lappe, having been transformed into silver was slightly twisted. In this phase the aim was to ensure that the fibres could be stretched without problems.

17

Although a “mule-jenny” could produce some 585 kg of yarn in a year, a self-acting mule (as it was known) could yield up to 810 kg. Continuous spinning, a technique from the late 19th century, was able to reach a figure to 1620 kg: twice as much.

18

Spinning

Spinning is central to the cotton manufacturing process. Most workers were taken up by the spinning machines, and these devices dictated the dimensions of each factory. From 1885 onwards, the continuous spinning machine replaced all other models, as this new model operated continuously, both stretching and twisting the yarn at the same time.

During the 19th century, the job of spinning was shared by men and women, when using mule-jennies, bergadana jennys and self-acting mules. The mass introduction of continuously-operating devices at the end of the century saw a major increase in the number of women workers, on far worse wages than the men, a fact that led to considerable social unrest in the Ter basin.

On leaving the continuous spinning jenny, the yarn is then passed through a series of other mechanical devices, and those used depended on the end purpose of the yarn – weaving, dying, or rope-making.

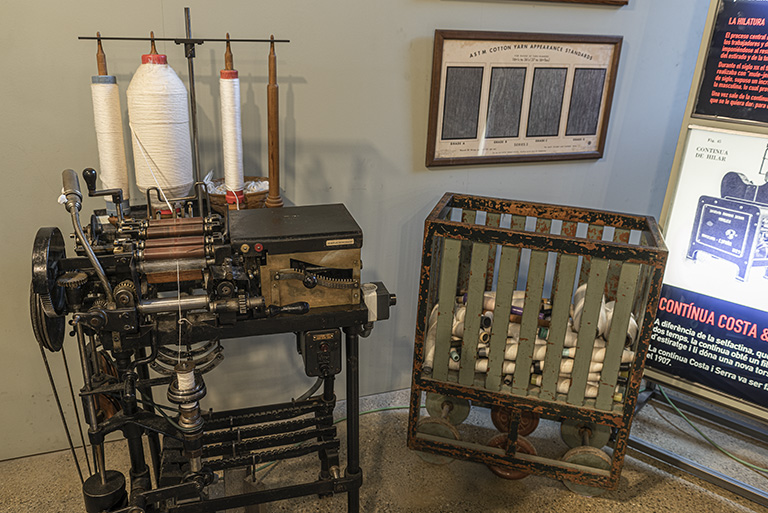

The Costa & Serra Continua Spinning Jenny

Unlike the self-acting device, which performed the spinning process in two phases, the continua, as it was known in Catalan, produced a continuous thread using stretching equipment, while twisting it once again.

The Costa & Serra Continua machine was manufactured in Manlleu in 1907.

19

Twisting the Thread

In order to obtain a stronger thread, two or three strands were used. These must first be brought together in a parallel fashion in a special rounding machine, before being twisted together by the continuous spinning jenny.

20

Bobbin Filling Machine

During the process from the production of the thread to when it finally becomes a woven fabric, a support used to hold the thread changed several times, depending on its use: for dyeing, for weaving, for transportation. This machine was used to change the way the thread was held, which went from the skein, then to the spool, before going to the loom.

The Skein Press

Another option was to make skeins of the yarn that were produced by the spinning process. The press brought together a considerable number of spindles that held the cotton together in the form of skeins. Before the modernization of dyes, the yarn was dyed in the form of skeins, using a traditional immersion system.

21

Businessmen

Businessmen had to invest capital in their factories and constantly update their machinery in order to increase productivity and sell their goods at lower prices. The inherent risks in such ventures led many co-operate with each other, the best example is in the collective project of the industrial canal. The parallel co-existence of abundant, cheap energy, low salaries and limited social conflict was to induce other capital investors from Barcelona and Vic to establish their businesses in Manlleu.

22

The Concentration of Capital

The years 1850 to 1875 bore witness to a rapid process of industrial concentration. During this period, the number of registered manufacturers in Manlleu went into a gradual and constant decline, while the wealth of those who survived grew considerably. The latter were to form companies that were to swiftly push aside smaller manufacturers, many of whom went on to become salaried employees, and cottage labour, which by then was mostly limited to weaving, became merely a marginal occupation.

23

Coal and the Railway

The intensive use of water was Catalonia’s alternative to its lack of coal for steam engines. Importing coal from Wales and England and transporting it to inland Catalonia led to high costs, making it an unviable option. This lack of local coal led some to believe that the future lay in coal from Surroca and Ogassa. To transport the mineral from these relatively nearby areas, the Granollers - Sant Joan de les Abadesses railway was built. It was completed in 1880. Although this coal failed to live up to expectations, given the high costs involved in its extraction and its low quality, the train allowed the textile industry to expand from the mid- to the upper Ter, as it improved the transportation of cotton, cloth and goods.

24

Population and Urban Growth

Factory work in the factories attracted many labourers from nearby towns, especially from Lluçanès and Collsacabra. Between 1842 and 1900 Manlleu went from 1,991 inhabitants to 5,823.

In order to accommodate newcomers looking for work in the town, apartment-type housing multiplied and the population moved to the streets that were built near the Ter. By 1883, Manlleu’s appearance had become highly urbanised, despite the influence of the local agricultural economy.

25

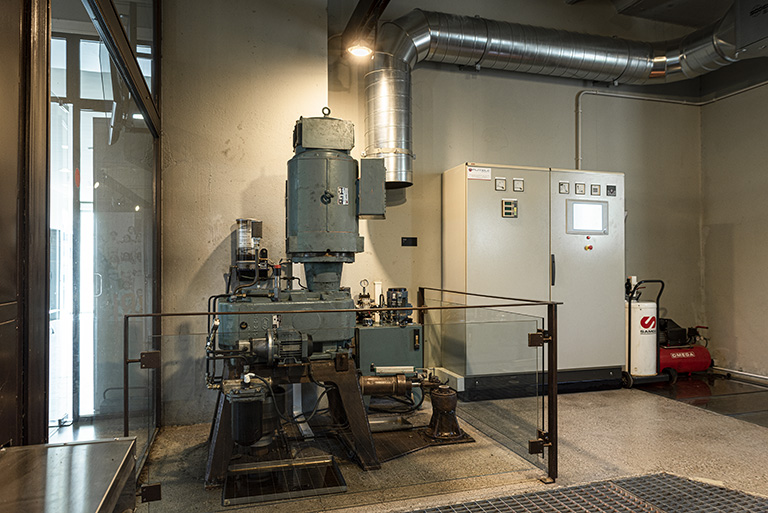

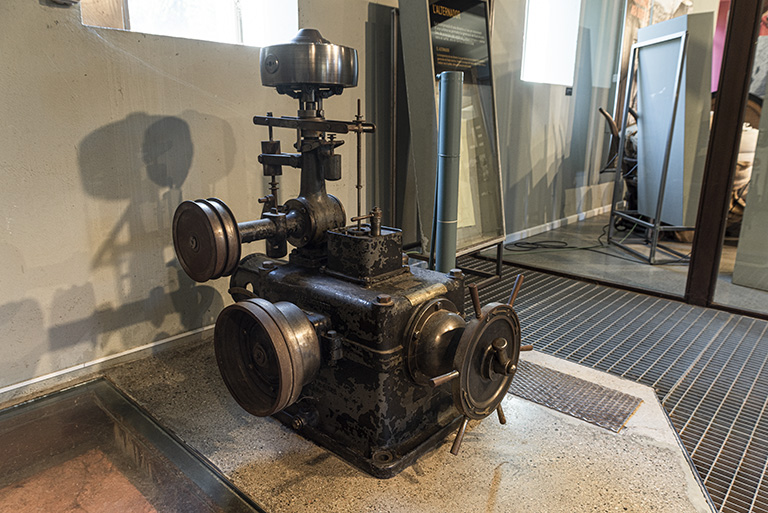

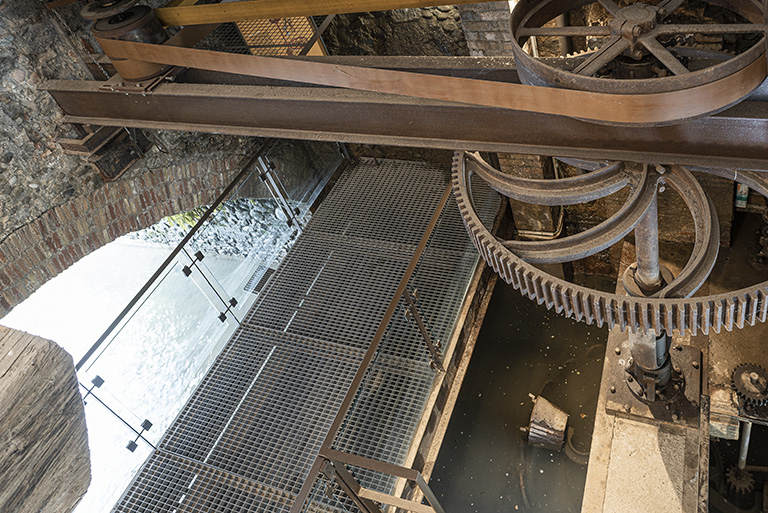

The Turbine, the Heart of the Factory

Hydraulic turbines were the mechanisms used to obtain the energy needed to power the spinning machines and later to obtain electricity. These turbines replaced the traditional hydraulic wheels that were used until well into the 19th century.

One of the first hydraulic turbines was installed in Can Sanglas in the Ter basin around 1860. It was a Fontaine-type turbine (known as a got a perxes in Catalan) with a 12 horsepower capacity and it was manufactured by the Girona company Planas, Junoy, Barné & Company. A major flood in 1940 left the inlet canal badly damaged and the turbine was shut down until it was restored in 2007 (although there had been an earlier attempt repair it in 1963). It currently operates for demonstration and educational purposes.

The turbine operated the machinery located on the two floors of the factory by means of a transmission shaft system.

26

The Fontaine Turbine

The Fontaine is a turbine of French origin, and it adapts well to the irregular river flows that are typical in the Mediterranean region. It is equipped with a regulator that adjusts the number of water inlets to fluctuations in the river flow. In order to work, the turbine needs to maintain a constant pressure and therefore requires a minimum constant water flow. So, depending on the amount of water available, adjustments can be made to the water that reaches its blades (1) by the use of cylinders (2), which, when spinning, either wind up or unroll a leather belt (3) that either impedes or opens up the water flow.

These turbines were custom-built by the Girona company Planas, Junoy, Barné & Cia. Between 1855 and 1918, and they made the mechanization of the cotton industry possible in river factories on both the Ter and on the Llobregat.

27

Transmission Shafts, the Central Core of the Factory

The force of the water was transmitted from the turbine to the factory machines by means of an ingenious mechanical transmission system, which is generically known as a transmission shaft. Each factory had its own transmission shafts and they were either highly complex or extremely simple systems. However, the ingenuity of the technicians and mechanics of the factories was always on hand. Operation and maintenance were essential aspects in the factory, and the turbine mechanic and the greaser were responsible for these tasks. The operation of the factory was totally dependent on their work.

In the recovery of our industrial heritage, transmission shafts have received little coverage, unlike the machines that received their power, and many disappeared with the advent of electricity and the application of electrically powered motors to factory equipment.

We have added a glossary of terms for mechanical transmission systems. Most of them are found in our transmission shaft. This glossary is not exhaustive and other terms could certainly be added. However it does include the use of local names.

Embarrat - Transmission shaft (drive shaft, or axle) (1)

This piece of equipment is usually shaped like a bar, and which rotates in the mechanism while supporting partial torsional and bending forces. The hemispherical hole in the axles is so that a pulley or cogwheel may be fixed to a shaft by means of a threaded screw was known as a cul de got.

Arbre - Shaft (2)

In the transmission shafts, this was the vertical shaft and the main axle of the entire unit.

Pulley (3)

This is a small diameter cylinder that rotates on a concentric axle with its geometric axis. The movable pulley was known as a “politja boja” or “morta” - a crazy or dead pulley, and it rotates regardless of the axis on which it is mounted. A fixed pulley rotates together with the shaft. The central part of the pulley, which is fixed directly to the shafts or shafts was known as the pulley button, or “botó de la politja”. The slightly curved shape of the external profile of the pulleys in Catalan was known as “esquena d’ase”, - the donkey's back.

Dau (4) - Drive Shaft Housing

This was a set of equipment consisting of the housing and the drive shaft bearings. The bearings are a piece of metal or wood a shaft or rotating axle rests on. Currently the bearings are of balls or rollers that involve easier maintenance. This was once one of the most sensitive points of the factories. Lack of proper lubrication could lead to damage, which was known as an enfarregat. One of the devices used for the continual lubrication of the bearings was a small glass or metal can called a xatel that was filled with oil and refilled from time to time. Factories consumed large amounts of oil every day.

Dineret de la turbina - Turbine Support Bearing (5)

An axle support bearing with a circular friction surface that supports the turbine spindle and the drive shaft.

Cadireta - Hub (6)

This is a piece of iron that is used to support the housing of an axle or transmission shaft. The slot in the hub that is used to centre the axle in its proper working position was called a Scotch yoke, or in Catalan, the trau colís.

Reenvio - Transmission Pulleys (7)

Factory technicians gave this name to the set of pulleys and belts that were used to change the axle rotation direction.

Angle sprocket (8)

This is a unit of two pinions that engage with each other at a 90 degree angle. The teeth of the pinion are the parts that drive the wheels. They may be made of metal, cast iron or wood.

Belt (9)

A band, or strip, made of leather or similar material. In Catalan it is referred to as an endless belt, which is a strap where the two heads are linked together, and which, when passing through two pulleys, two cylinders or two cones, transfers the movement of one to the other. A process called the afuat – or sharpening, consisted of modifying the ends of the strap to ensure that it adhered better. The glue used was called horsetail or cua de cavall in Catalan.

Mànega - Lever (10)

A piece used to join the shaft of a transmission shat. A pulley or sprocket was attached to the shaft or axle, usually by pressure (action called manegar).

Clutch (11)

A mechanical friction device that connects two sectors of the axle transmission. The main sprocket wheel (magrana) is a flat, toothed wheel that was usually used to connect the turbine to the steam engine.

Cogwheels (12)

A flat transmission wheel set from 0º to 90º. The gear wheels engage, ensuring that the transmission is optimal.

Endless Screw (13)

A transmission shift pinion set at 90 degrees with excellent speed reduction capacity.

Peg (14)

A piece used to attach gear wheels, angle wheels or pulleys to shafts or axles. The notch is the slot where the peg or pin is inserted. The nose of the key is the outer part used to unlock it.

The original items used in this display in the Ter Industrial Museum come from several different industrial facilities: the Miarons mill (Manlleu), the Molí d’en Saleta mill (Masies de Voltregà) and the Llana de Martinet factory (Cerdanya).

28

A Heritage Regained: the Wool Mill of the Mountains

The Vilarrubla de Martinet mill in La Cerdanya owned this range of carding machinery, which was produced in 1875 in the French city of Rheims. The Ter Industrial Museum recovered and restored this once typical device for our rural manufacturing heritage.

The mill produced skeins of wool for use in jerseys and tapestries.

29

Two factors explain why this mountain industry existed: The proximity of the raw materials and the demand for quality woollen products. Provided with the basic resources (wool, and energy produced by water wheels), these mountain mills have survived to this day, alongside modern city and riverside mills.

30

Wool from mountain sheep arrives at the mill dirty and full of impurities and must therefore be washed before being processed. Once dried in a specially designed area, it is taken to the opener, where the fibre is shaken and opened, before moving on to a carding machine that was known as El Diable (the devil), where the wool is divided and sponged. From there it moves on to the three carding processes. When it emerges from the carding machine, the wool is ready for the self-acting mule, where it is transformed into yarn.

31

Living with Risk

Too often, work in the riverside mills brought with it a considerable risk; whether this came from working with machinery, from fire, or from periodic flooding. All the workers were directly exposed to these dangers.

32

The Teeth of the Machine

Mechanisation in the factories meant a new relationship between man and machine. The vast number of exposed belts, pulleys and sprockets, the hazardous work on the Diables and other carding devices, covered with moving needles, added to the effects of exhausting working hours and the abundance of child labour, all of which took a high toll in terms of accidents and injuries.

33

When the River rose

At times, the river rose dramatically. The towns along its banks, and the factories which used its energy, were then often overwhelmed by a raging torrent.

34

Fire in the factory!

Fire periodically threatened the very existence of the textile mills. The accumulation of waste and raw materials and finished yarn, and the fact that many items were made of wood, meant there was a constant risk, aggravated by the heat developed in the pulleys, belts and engines, or the sparks produced by the card needles, or a cigarette.

35

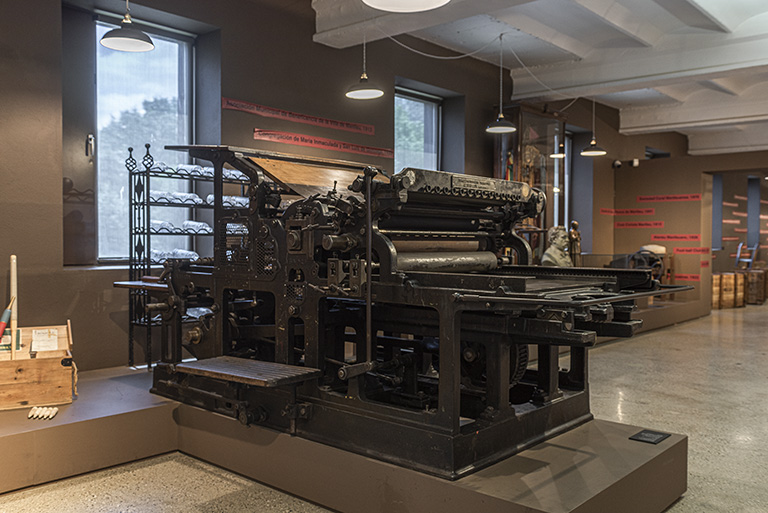

From Mechanics to Machine Builders

The origins of the Catalan steel industry are directly connected with the industrialisation of textiles. Many of the most important machinery manufacturers of the 20th century had their origins as repair and construction workshops for textile machinery. In the early years of industrialisation, this machinery was purchased from overseas.

Josep Sanglas and Josep Serra are the finest example of this close relationship. One was a cotton merchant, the other a mechanic, together they were to manufacture continuous spinning machines and set up what was, until the 1960s, the largest Catalan textile machinery company.

36

Can Serra

The company was founded in 1902, when Josep Serra Sió, a locksmith from Roda de Ter, formed a partnership with Andreu Costa, a mechanic from Manlleu. In its early years, the company repaired machinery for textile businesses in the area. Serra's character and technical genius did not go unnoticed by a man of insight, in this case, Josep Sanglas Alsina, who, in 1913, provided the capital necessary to found Serra Ltd., which specialised in manufacturing machinery for the spinning industry.

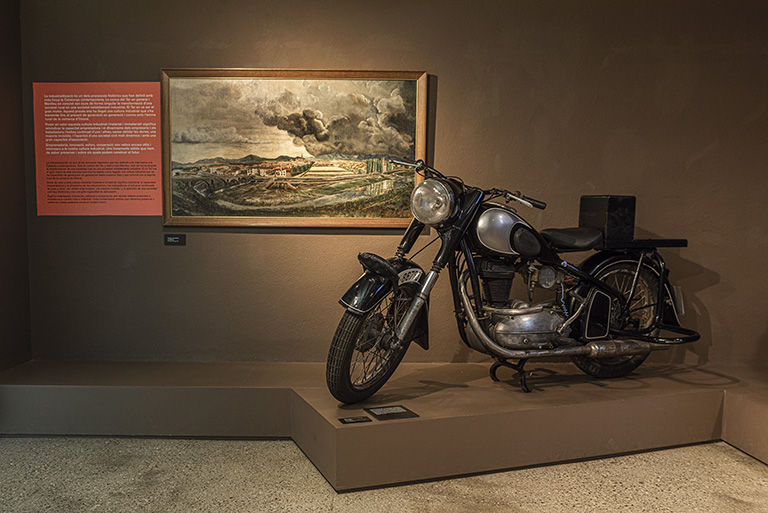

37

Sanglas Motorcycles

In the early 1940s, Martí and Xavier Sanglas, the sons of the Manlleu industrialist Josep Sanglas i Alsina, set up Talleres Sanglas SA, which manufactured motorcycles. In 1944, the first model of the Sanglas brand appeared, and over the years it was to become one of the most prestigious brands in the state. Although the factory was always located in El Barcelonès, the roots of the Sanglas bikes were always in Manlleu.

38

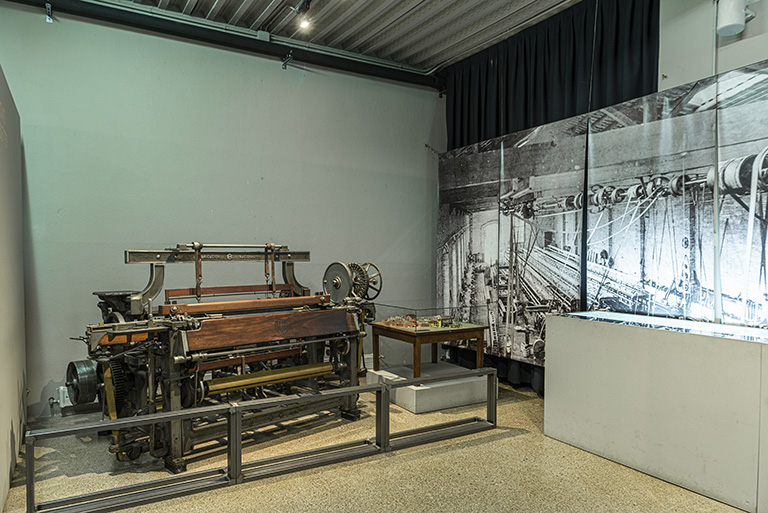

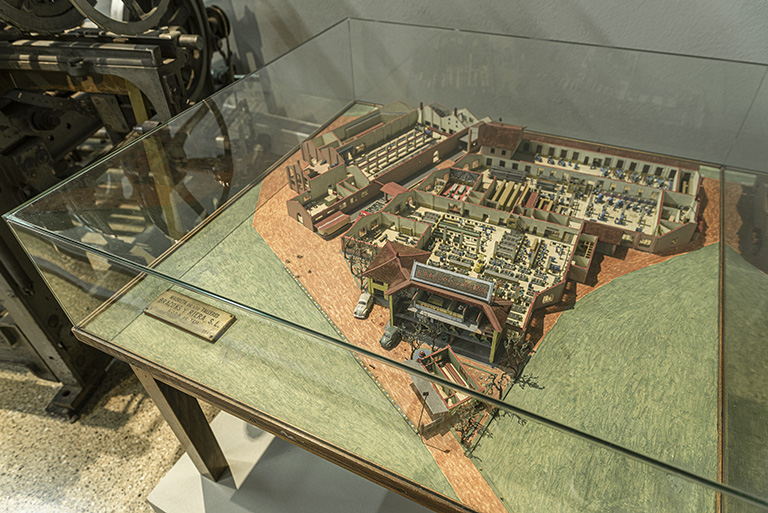

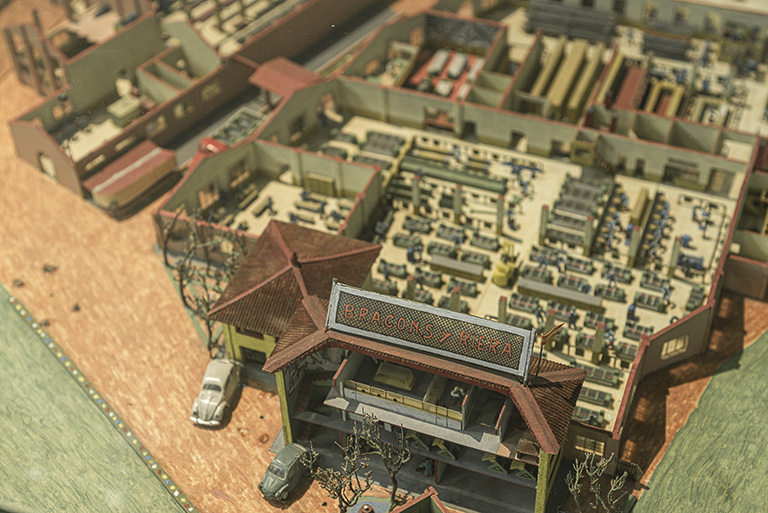

The Bracons and Riera Looms in Roda de Ter

The company opened as a repair workshop for textile machinery began in 1855. Growing industrialisation in the area led its owners to begin manufacturing the machinery themselves. In 1917 they opened the foundry where they were to build their first looms. Twelve years later, the first semi-automatic loom to be built in Spain was made in this factory. The machine won a gold medal at the Barcelona International Exposition of 1929.

39

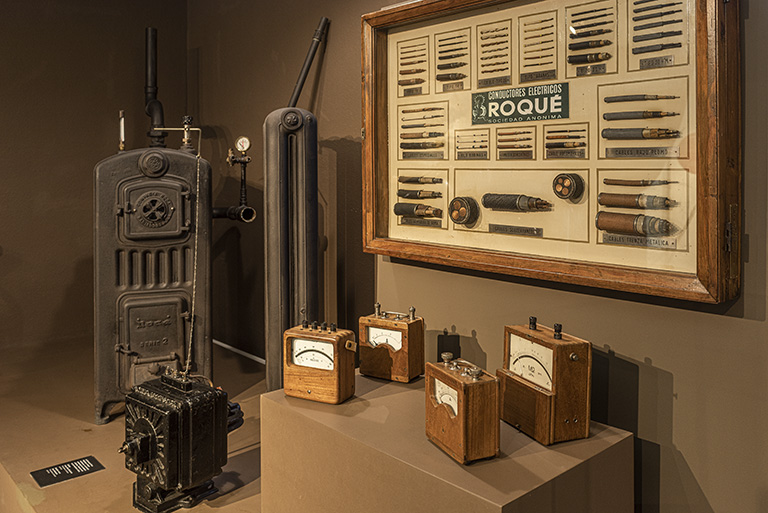

The Fraguas del Ter Foundry

In 1915, Eudald Carandell Puig, together with Artur Roqué and J. Planas of Manlleu, opened a mechanical workshop in the Carrer de Sant Jaume and a small foundry in Sant Martí Xic, near the Ter. Eudald was married to María Català Benito, whose family owned the Talleres Català workshops in Torelló, and he was a specialist in the manufacture and repair of loom accessories. In 1922, Joaquim Carandell Català, the mechanic at Can Serra, joined the business. Fraguas del Ter was to specialise in the manufacture of parts and spares for looms, at its workshops in Manlleu and at the Altafaja foundry in Vic, which was relocated in 1935 to the Sucre industrial premises in Manlleu, near the train station.

40

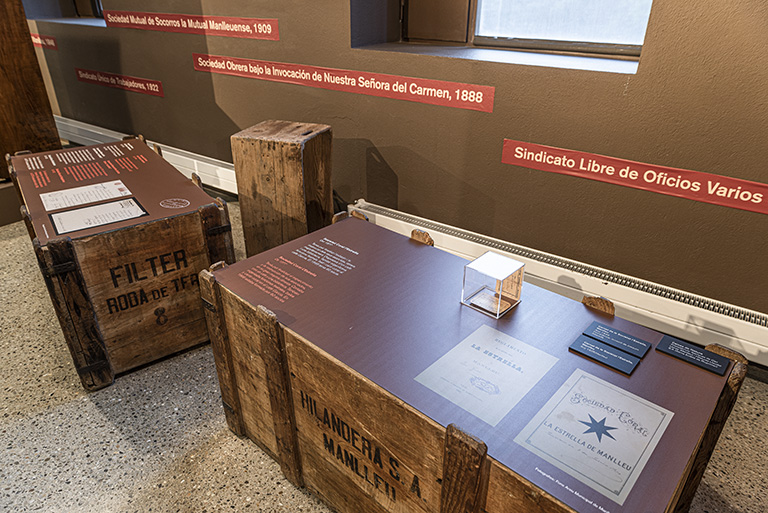

Industrial Society. 1845-1935

New conditions and ways of life and subsistence associated with the new capitalist economic system, new social groups, new industrial projects, new forms of cultural, political and class association (choirs, trade union groups, mutual aid bodies, religious groups, etc.), new conflicts - in short, a new and highly active society, in constant movement and transformation arose. This is an example of how industrialization has transformed the world, Catalonia and, of course, Manlleu and the Ter basin.

41

Manufacturers and Workers: the New Leading Characters

The new industrial society that was created in the mid-19th century was mainly urban, and it had two main figures: manufacturers and workers. The former were highly enterprising, while the latter, en masse, constituted the mainstay for unprecedented economic growth. This was a world controlled by men, but it was also one where women, in the shadow of male dominance, took on a highly significant role. In fact they were the main workforce in the textile factories of the Ter for more than a century.

42

In this booming world, some men and women played their part in new economic, social improvement projects, while many others suffered the consequences of industrialisation without being able to do much about it. Manufacturers and workers, as well as farmers and tradesmen, were forced to adapt to this new situation.

43

Josep Serra i Sió

Josep Serra i Sió was born in the town of Roda de Ter in 1877. His father was a weaver and his mother was a seamstress. At the age of 10 he was already an apprentice at a spinning mill in Roda, and shortly afterwards he went to Terrassa to work in a metallurgical company, where he became a journeyman only a few years later.

In 1902 he became partners with the Manlleu mechanic Andreu Costa i Pagès and created the company Costa i Serra, which was initially dedicated to the repair of machinery, but which soon began producing spinning jennys. In 1913, he created the Serra Public Limited Company, which manufactured all types of equipment needed for cotton spinning. Can Serra became the first Spanish company to build machinery for the textile industry and one of the most significant companies in Manlleu, those who worked there were said to “have it made for life”.

Josep Serra's entrepreneurial ability led him to participate in many other industrial projects, including the creation of Roqué Electrical Conductors. Serra remained in charge of the factory until 1940, until one of his eight sons, Josep Serra, took over. He died in Barcelona in 1959 and in 1964 the company was acquired by foreign capital.

44

The Roca Family

In 1830, the locksmith Ignasi Soler set up a small ironsmiths in Manlleu. Making the most of the town’s industrial impetus and with the help of his son Maties, this blacksmith’s shop became a workshop for the construction, repair and maintenance of machinery used in Manlleu’s textile industry. In 1880, Maria Soler, the only daughter of Maties Soler, married Pere Roca, a blacksmith from Montcada with experience, having worked in metallurgical companies in Barcelona. The Roca workshop soon became an important company in Manlleu. Between 1880 and 1890, the four surviving children of the Roca Soler marriage, Angela, Maties, Martí and Josep were born.

The children learned their trade in their father's workshop from an early age. They were later sent to metallurgical companies in Barcelona to train, away from the family home. Pere Roca died in 1910. The Roca brothers were restless and enterprising young men. They opted to enter the heating sector, and took on the challenge of becoming the first company in Spain capable of forging radiators. To this end they travelled to France to work and learn from companies operating in the sector. On returning to Manlleu, and after several attempts, the Roca brothers managed to achieve their goal, with their products making their mark in the growing domestic market.

In 1917 the company moved to the town of Gavà to facilitate logistics and communication. The Roca brothers expanded and diversified the business, and were to make the Roca brand a world leader in the construction of radiators and vitrified porcelain bathroom and sanitary products.

45

The Puget Family

The Puget family represents the entrepreneurial and innovative spirit of those manufacturers who were leaders in the early days of industrialization in the Ter basin. This family originally hailed from Osseja, in the French Cerdanya region, and from where Francesc Puget i Montfort emigrated to Vic sometime around 1826. By 1834 he owned an important cotton yarn and fabric factory, which was powered by mules. Rafael Puget Terrades, his son, was also born in Osseja in 1823. His father sent him to study in Manchester (the birthplace of the cotton industry) for two years.

Francesc soon saw the industrial potential of the River Ter. In 1841 he rented the Can Barola factory in Manlleu, which was powered by a water wheel. At the same time, and with two partners, he acquired the surplus water concession from the Teula dam, where the Manlleu Industrial Canal was built, and together they planned the Three Factories. Puget was to keep the middle factory. This project was linked to the creation of the Manlleu Industrial Canal, whose owners’ company was founded in 1848.

Francesc died in Vic in 1868 and his son Rafael took over the business. Rafael Puget continued to invest and participate in industrial projects linked to the Manlleu Canal, such as the company Almeda, Sindreu and Company, the Seda Factory, and Cal Blau. Rafael Puget i Terrades built a large house in Manlleu, in Dalt Vila, a testament to his family's economic power. Construction on the house was completed in 1888. Rafael died in Manlleu in 1886. His eldest son and heir was Rafael Puget Munt, who was born in Manlleu in 1873, however he was not a noteworthy industrialist. He moved to Barcelona, where he became a typical bourgeois figure in Barcelona’s Eixample district. Josep Pla was to make him the leading character in his novel Un senyor de Barcelona. (A Gentleman of Barcelona).

46

The Rusiñol Family

Jaume Rusiñol i Bosch was born in Manlleu at sometime between 1808 and 1810, and he died in Barcelona in 1887. Rusiñol was involved in the cotton trade in the Catalan capital, where he went to live. He had very close ties with Manlleu, which at that time was already one of the main cotton production centres in the country. In fact, he was one of the first textile pioneers from Manlleu, with the creation of the company that owned the Can Puntí factory, which opened in 1853. In 1879 he bought the Can Remisa factory, which became the most important in Manlleu.

Jaume Rusiñol had a single descendant, Joan Rusiñol, who ran the family business in agreement with his father until his death in 1883. Joan’s eldest son, Santiago Rusiñol, then took over the Manlleu factory, a job that he had been brought up to do. His passion was art, however, and a year after his grandfather’s death in 1887, his brother Albert Rusiñol took over its direct management, in agreement with Santiago.

In the following years Albert Rusiñol consolidated the factory and especially the factory town, with the construction of new buildings, including the owners’ mansion, Cau Faluga. This home was to be the starting point for several trips made by Santiago and the site of several cultural and political events organised by the two brothers. Albert Rusiñol was to become an important industrialist and a politician who wielded certain influence: he represented Vic and Barcelona several times, he was a senator for Tarragona, the President of the Regionalist League, the President of the Promotion of National Work, and the founder of the Manufacturers’ Association of Manlleu and the county.

47

Ramon Mas Costa

Ramon Mas was born in Vic in 1882. He was the son of a gardener, as a child he began to roam among the vegetables in the orchard in the farm of Can Tinoies, in Santa Eugènia de Berga. A few years later he met Maria Pou, who also a gardener from Vic, and who came from the Clos orchard. Shortly afterwards they married and decided to move to Manlleu, where they were to run the orchard of the Can Sanglas factory, which had begun operating in 1872. For some years, both the orchard and the house had been unoccupied. Their dealings with the Sanglas, the owners of the factory and the orchard, were established in the usual manner, they would work the orchards and live on the property and the profits were shared evenly. Mas became was to become the owner of Can Sanglas.

The vegetables and the nursery do not follow timetables and Ramon and Maria worked long hours. On Mondays they would go to sell their wares at the Manlleu market with their horse and cart, and on Wednesdays at the Torelló market. However, at the house on Carrer del Bisbe Aguilar, right next to the factory and the orchards, there was almost always a line of clients waiting to buy vegetables, washed and ready to eat.

Ramon Mas and Maria Pou had five children, three boys and two girls. Their heir, Joan, continued the family business, and continued to work, along with his wife, Rosa, who had exchanged textiles for vegetables. Ramon Mas died in 1957.

48

Ramon Madirolas

Ramon was born in Manlleu in 1856 to a wealthy family, the owners of the Madiroles farmhouse. He studied in Barcelona and at the Collell seminary - near Banyoles. In 1882 he married Pilar Torrents with whom he had three daughters and four sons. He was widowed in 1898, and in 1912 he remarried Dolors Casas, who also left him a widower in 1918.

Madirolas was a highly energetic man. He was influenced by the changes of his era and implemented innovations on his properties, especially in the cultivation of wheat and potatoes, and which earned him both international recognition and awards. He was also behind the commercial exploitation of a spring on his land, which he used to market mineral-medicinal water, and he converted his manor house into a spa-type health resort.

His social activism was marked by his deeply-held religious beliefs. His activities and projects included the promotion of the construction of the Puig-agut Sanctuary between 1883 and 1886, and he participated in the founding of the Catholic Youth Society in 1877, and in the arrival in Manlleu of the brothers of the Christian Schools of La Salle. Madirolas was noted for the relationships he maintained throughout his life with the country's political, religious and cultural elites. His friendship with General Valeriano Weyler is particularly well known. Madirolas died in 1927 and was buried, together with his family, in the tomb built in the Sanctuary of Puig-agut.

49

Filomena Sanglas Guiu

Filomena was born in the farmhouse of Can Sanglas in the Saderra (Orís) neighbourhood, on 19 March 1853. She lived there with her parents Joan Sanglas and Teresa Guiu until she married Jaume Solà Alou in 1880 who came from Tavertet. Once married, they moved to live in his home, in the Llobet farmhouse, which is also in Tavertet, near the River Ter and the monastery of Sant Pere de Casserres.

Filomena and Jaume had five daughters and four sons. Like all women, in the historical documentation where she was registered, she appears as “without profession”, or sometimes as “housewife” and in some entries, as “work appropriate to her gender”. We do know, however, that Llobet Filomena did what she had also seen her mother do since she was a child: raising her nine children, looking after the food and health of all the members of the household, washing clothes, sewing, and taking part in field work and in the care of livestock. Her family remembers her as a spinner, which is an activity that she most certainly had to combine with all her other domestic chores.

Her husband died in 1905 at the age of 52. Shortly afterwards, Filomena moved to the home of her eldest son, Josep. He had built the Solà farmhouse in Sant Martí Sescorts (l’Esquirol). During the last years of her life, Grandma Llobeta, a nickname Filomena was known by, and which referred to her origins, was mainly engaged in spinning by hand and collecting medicinal herbs from the area, which she then sold to nearby markets. She died on 23 February, 1945, at the age of 93.

50

The Textile Workers of the Ter. An Invisible Majority

By the end of the 19th century, women were already in the majority in the factories of the Ter. Armies of spinners, auxiliary workers and apprentices all worked on the niddy noddys, the roving frames, on the spinning machines and the bobbins. In innumerable tasks, and they were often despised and relegated to the lowest rung in the employment hierarchy. They were insulted with names such as ‘bed bugs’ and ‘manufacturers’.

51

At Home and in the Factory: the Double Day Shift

Thousands of women from the Ter spinning mills had to combine work in the factories with domestic and family responsibilities. The inclusion of women into the industrial workplace did not change the family roles associated with gender. Women had to continue doing their household chores outside the factory.

52

It was not until 1900 that a law was first passed that banned women from being employed within a three-week period after childbirth. This absence was unpaid and it only forced the company to retain the mother’s job during this period of leave. In 1907, the postpartum period was extended to six weeks. It was not until the Second Republic (1931) that compulsory maternity insurance was introduced, as well as a six-week paid postpartum leave. However, the existence of these laws did not always presuppose compliance with them.

53

Even though the first law banning women from working at night was passed in 1912, it was very common for women who had greater family responsibilities to work more on the night shift. It was a means they used to reconcile work in the factory with their second workday in the home.

54

The Opposition of the Workers’ Movement to Women in the Workplace. The Case of Manlleu

Male workers were suspicious of the entry of women into the factories and strongly opposed this move, and sought to defend their jobs and their better wages. In the larger industrial centres, unlike the planned industrial communities or the smaller centres, labour was more organized and this slowed down the replacement of male by their female counterparts. Manlleu, as an important industrial centre was an example of this.

55

Factories for Women

In terms of spinning, the tasks involved were divided into three large groups: preparation, which was mainly performed by men; spinning, a task undertaken by both men and women, although most workers were women and almost all the workers were female in the finishes. The specialized trades were reserved for men: carpenters, bobbin workers, turbine workers, locksmiths, greasers, officers. The hierarchy was strict, and women, who formed the majority of the workforce, occupied the lowest level.

56

During the working day no substantial differences existed between women and men. At first, the days were exhausting. Over the years, and due to the force of social protests, the days became shorter. In 1902, the legal working day was 66 hours a week. In 1913 it was set at 60 hours, and with the General Strike of the Canadenca in 1919, it was finally established 48 hours.

57

Women earned lower wages than men who did the same job. In 1900, the Local Board of Social Reforms of Roda de Ter passed a law for men to be paid 3 pesetas, women 2, and children 1.5 per day. In 1914, in the Almeda & Alemany factory in Vila-seca (Sant Vicenç de Torelló), a female spinner earned 20 pesetas a week, just half the salary of a her male counterpart.

58

The Paths of Women

Many women workers originated from the dense network of farmhouses in the County of Osona. On the way to work, they talked, prayed, sang, but often had to avoid male harassment. Over the years, these women gave shape and identity to the paths they walked. Some examples are the Camí de la Paciència, which connected Sant Pere de Torelló with the Vila-seca and Borgonyà factories, or the Camí de les Xinxes, which connected Folgueroles with the Roda de Ter factories.

59

One dramatic example of the violence that women had to endure was the case of “The Killings of the Cós”. On 22 August, 1858, six women workers, aged between 10 and 23, were assaulted by two men in the area known as the Cós rocks, on the Camí de les Xinxes. Three of them were killed and the others survived their injuries.

60

On March 23, 1882, an announcement was made by the mayor of Roda de Ter that mentioned the insults hurled at female workers at factory entrances and exits. The document threatened legal action against those responsible. This tells us to what extent this kind of verbal aggression was a common practice with respect to women workers.

61

Gaspar Vigué

Gaspar Vigué was born in Torelló in 1873. His father, Lluís Vigué, came from L’Esquirol and was a labourer. There were five brothers in a very poor family. Gaspar began working in a textile factory around the age of eight, where he eventually got a job as an apprentice spinner. The men who worked on self-acting spinners chose their own apprentices and paid them their own salary directly. A few years later, Gaspar also became a spinner, and was responsible for his own self-acting device.

Gaspar Vigué married Júlia Manent in the parish church of Sant Feliu de Torelló, in 1896. The following year they had their first child, Vicenç Vigué. The last years of the 19th century bore witness to serious conflicts between workers and employers in the factories of the Ter. One of the reasons was the introduction of continuous spinning jennys in the textile factories, and with them the arrival of women in jobs that until then had been designated for men. The spinners, who were proud of their trade, considered it an attack on their status.

Gaspar Vigué was one of the workers from the Ter basin, who in March 1901, staged violent protests against a lockout – a factory closure implemented by the owners to counter the strikers, leaving 14,000 workers without work. On 11 March, Vigué died from a gunshot wound during clashes with the police in Torelló. The events were widely reported by the national press and Vigué became one of the martyrs of the labour movement. His daughter was born eight months after his death.

62

Francesc Abayà Garriga

Francesc Abayà was born in Barcelona on 22 April 1844. His father was a linen weaver. He was a dyer, and between 1870 and 1871 a member of the Board of the Society of Journeymen Dyers of Barcelona. In 1872 he took part in the founding congress of the Manufacturing Union. He became a member of the board and was appointed as the editorial secretary of the magazine La Revista Social. During this period a request was made to the Constituent Assembly of the First Spanish Republic for improvements in working conditions, including the eight-hour day, free and compulsory secular education and a ban on the employment of children under 12 years of age.

In 1880 he was in Manlleu, and was linked to The Progress Choral Society of Manlleu in a project for creating a workers’ training centre. By late 1883 he had moved from Manlleu to Vic, where his daughter Maria was born. Nine months later, in 1884, he returned to Barcelona, where he became intensely involved in trade union life. During this period Abayà was a good example of the radicalization process in the Catalan labour movement, and he went from holding reformist positions to becoming an anarchist. In 1892 he was arrested for his involvement in the general strike. His son Galileo was born in Barcelona.

In 1894 Abayà returned to Manlleu and he moved to the Carrer de Sant Antoni with his wife and children. In 1900, as the leader of the Regional Workers’ Union of Arts and Trades of the Conca del Ter, he tried to reorganize the unions through the then defunct Federation of Workers of the Spanish Region. In this process he backed what was known as the Manlleu Manifesto. In 1911, at the age of 66, he left Manlleu again, together with his wife and children. He died in Barcelona in May 1917.

63

Josep Lladó

Josep Lladó was born in 1880 in Olost de Lluçanès. His family moved to Manlleu soon afterwards. The industrial capital of Osona attracted many workers from the surrounding mountainous regions at the time. Lladó was the eldest of twelve brothers. He started working in the Can Puntí factory when he was just 8 or 9 years old. His father died when he was very young. Lladó became a spinner, a job in which men still predominated in Manlleu, thanks to the force of the working men’s movement. He was later to work for the company Roqué Electric Conductors.

Josep Lladó helped to transform the Manlleu Mutual Bread and Groceries Cooperative into one of the main consumer cooperatives in Catalonia. It initially focused its activities on Manlleu, but its influence eventually spread to the region of Osona and then throughout Catalonia. Lladó was in fact one of the most prominent figures in the Catalan co-operative movement, along with another man from Manlleu, Joan Codina.

In his political life, Lladó was a councillor on the Manlleu City Council for the United Left Front during the years of the Republic, and was mayor during the events of October 1934. Later, and in the middle of the Civil War, he was appointed mayor on behalf of the Socialist Union of Catalonia. Lladó was forced to flee after the war. He eventually went into exile in France, where he died in 1963, in the city of Hyères. His colleague in the cooperative and Socialist movements, Joan Codina, chose to stay in Manlleu. He was executed by firing squad on 3 March, 1939.

64

Maria Roma. A Biography Recreated

Maria was born in Sant Boi del Lluçanès in 1872. When she was still a child, she left for Manlleu, together with her parents and five siblings, where the factories were offering new job opportunities. One of her father’s brothers had already moved into the town, and he offered them a room in his house for a while. The manager of the factory, Can Rusiñol, where his brother worked, had also promised to give them work: her father operated carding machines, her mother worked at the niddy noddy, while some of her brothers were apprenticed to spinners.

She began work at the age of eight, helping her mother. The factory was full of women and children, and the day was exhausting: it began in the morning and it lasted for fourteen hours, including Saturdays. The road to the factory was one of the few moments of recreation, but darkness, sleep, and fatigue were often her companions on the journey. For the forty-odd years that she worked in the factories, the roads were the scene of fears, laughter, singing, problems and dreams that all faded away with the sound of the factory siren.

In the factory, Maria Roma began to learn, and was soon moved on to the roving frames. Wages were always meagre and lower than those of the men. Working in the factory did not relieve her of household chores (cooking, washing clothes, looking after children, etc.). She married a textile worker at the age of 19, and had six children, four girls and two boys. In 1934, at the age of 62, Maria died of lung disease, probably caused by factory blight and fatigue from working both at home and in the factory. She could neither read nor write.

65

Jaume Baulenas

Jaume was born in Manlleu in 1796, into a family of weavers. His father, who was also called Jaume, was a wool carder and he continued in the same trade. Baulenas married Petronilla Torrent, who was also from Manlleu, at the age of 16, and with whom he had five sons and two daughters.

The first years of the 19th century were prosperous for cotton weavers who, like Baulenas, found Manlleu to be the perfect location for the growth of their industry. In his workshop on El Carrer de Cortada, on the ground floor of his house Jaume Baulenas had up to six manual looms, which employed nine people, some of whom were his sons and daughters, who he put to work when they reached a working age. But the Peninsular War against Napoleon and the First Carlist War were to damage the business.

The demand for their fabrics slowly decreased. Factory-produced goods were being made ever-faster and cheaper. He finally stopped working with his last two hand looms in 1853. Baulenas, at the age of 57, had to start working in one of the first factories established in Manlleu, which used the force of the River Ter. Baulenas’ situation was not unique among the weavers of Manlleu, most of whom were forced to halt their work as small manufacturers and become workers in the new factories. In 1875 he died of lung disease at the age of 79. At that time there were only a few weavers who had managed to retain their domestic workshops in Manlleu.

66

Josepa, Pepeta, Vila. A Recreated Biography

Josepa was born in Roda de Ter in 1878. When she still just six years old, she began working in the Can Portavella factory, which was also in Roda and not far from the small flat on the Carrer del Sòl del Pont, where she lived with her parents, her two sisters and three brothers. Pepeta went to work on the niddy noddys during the night shift. She spent years there, with some changes in shifts, until with the advent of the continuous spinner, which replaced self acting machines, they moved her to another section. She was 13 years old. The work was hard, but working outside the home also freed her from the suffocating control of her parents and siblings. And she had friends in the factory too.

During those years, Pepeta and her companions were often insulted by men and children when starting their shifts. These new spinning machines did not require physical strength, unlike the self acting machines, and so women took over the work of the old spinners. This was the cause of several serious conflicts. What really hurt her was that they paid her half as much as a man. And it seemed to her that her male colleagues, would have liked to see her locked up in a house, taking care of her children.

On 1 May, 1900, Pepeta attended a workers’ rally at Can Guiu in which the Feminist Republican, Ángela López de Ayala was taking part. She thought that maybe one day things might change for women. Pepeta learned to read and write on her own, and at the age of 23 she married a mechanic from Manlleu who worked at Can Bracons. She had three children, who were born between 1902 and 1907. When Pepeta died in 1923, she was still working at Can Portavella.

67

Rosa Mas Albanell

Rosa was born in Manlleu on 4 January 1886. She was the daughter of Pere Mas, who was born in Sant Vicenç de Torelló, and who worked in Manlleu as a spinner for many years. Rosa's mother, Anna Albanell, also came from a textile family. Peter and Anna were married in 1885 and had seven daughters and three sons. Rosa was the eldest. As a very young girl she went to work in the Can Rifà factory (in Manlleu). In 1923, with thirteen other women, she worked on the roving frames, where there was only one man who, as usual, was in charge of the section. At that time, 138 workers were working in the Can Rifà factory, 67 of whom were women.

She was a woman with firm social and political commitments. In 1934 she joined the Group of Women Workers of the Left, which defined as its aims as the defence of freedom, the independence of Catalonia and the Republic, and improvement in the education of women. Her sister, Mercè Mas, was its president. After the Civil War (1936-39) they and seven other women were reported by a vicar and were accused of having a “bad background” and of participating in setting fire to the church during the war. The reports added that all the women had “leftist ideas” and that they had supported the leftist Popular Front movement. Mayor Casanovas Tona, however, declared that they could not be accused of having committed any criminal activities. Many local people supported the detainees, who were eventually acquitted. Shortly afterwards, Rosa returned to the roving frames of Can Rifà. She never left the family home, at 17 Carrer del Comte, and where she died on 28 December 1964.

68

Working to live

Industrialization rapidly changed the lives of working class people in both rural and urban environments, from trades and crafts to factory labour, with new, strict disciplines with respect to time and work, long working hours, child labour, food crises, poor housing conditions, and mass migration from the country to the city. The economic and social structure of towns and villages, such as Manlleu, Torelló and Roda de Ter were transformed in a very short time. And in the depopulated areas of these towns, on the banks of the Ter, industrial planned communities (the colonies), emerged around the factories. These were controlled by the manufacturers and often had the same services as industrial urban cities.

69

The banks of the river in Manlleu, between the Can Molas bridge and the Can Sanglas factory in the early 20th century. The Manlleu Industrial Canal stands out in this space with its numerous features; the factories that occupied the town’s river banks, the orchards, which shared this industrial landscape, the laundry areas, the women's work space, and the incipient streets of Baix Vila, where single-family houses were soon replaced by flats to accommodate the growing working-class population, who mainly came from the rural areas of the county.

70

The Rusiñol industrial community in the early 20th century. This settlement is located in the municipality of Manlleu, upstream and outside the town. Can Rusiñol was the factory owned by the family of the Catalan Modernista (Catalan Avant-garde) artist Santiago Rusiñol. At the end of the 19th century, Can Rusiñol, which was also known as Can Remisa, was the largest factory in Manlleu. The community was finished around at that time, and it included, in addition to the factory and the houses, a small church and the Rusiñol family mansion, Cau Faluga, which was named inspired by Cau Ferrat building in Sitges, also designed by Santiago Rusiñol himself.

Factories were located outside the town centres, along the banks of the river so as to take advantage of the hydraulic energy, and this led to the construction of a network of planned industrial communities along the course of the Ter. These made use of the river’s energy and also allowed manufacturers control all aspects of daily life, so ensuring social control and stability, factors that did not always occur in the most dynamic industrial centres.

71

Class Consciousness

The new social classes that emerged with the onset of industrialization were soon to become aware of the need to defend their interests and they began to organize themselves: workers sought to improve their poor social conditions, while employers sought to meet the workers’ demands and maintain the established order. Associations with cultural aims, cooperatives and health insurance agencies, trade unions, employers’ organizations, and occasionally political parties took on a previously-unknown role in social life. The church also played an important role, by promoting a Catholic-based workers’ association movement, as opposed to the grassroots, secular workers’ social organisation.

72

The Progress Choral Society of Manlleu

In an era marked by the persecution of workers’ social organisations and restrictions on the freedom of association, the Choral Society linked to the secular movement of Josep Anselm Clavé were of great importance. Despite their apparent cultural and recreational aims these groups helped to convey workers’ demands.

One of the first choral societies in the Ter region was created In Manlleu, in 1862, The Progress Choral Society of Manlleu. The organisation was based in the Carrer Call de Ter (now the Carrer Enric Delaris), it was an organization involved in republicanism and workers’ rights and was it linked to the movement fostered by Josep Anselm Clavé, who attended the society’s inauguration in person. In the 1880s the Choral Society moved to the Passeig de Sant Joan. The “choir” - the name by which this society is still remembered and which has been linked to the building on Passeig de Sant Joan that housed it for years, had a café - dances, conferences, songs, and rallies were all organized there, as well as theatre performances. One of the distinguishing features of the organization was that it sought to inform and to educate. The Choral Society created a secular school and a library as early as the 1880s. These educational aspirations were the source of serious clashes with Catholic sectors in the town. The Progress Choral Society disbanded in 1913 after upheavals stemming from both confrontations with the authorities and economic problems.

73

The Mutual Cooperative of Bread and Groceries

Industrialization led to a growth in the number of consumers, their dependence on trade and a worsening in terms of the living conditions of industrial workers. In this context, mutual support organisations, by the cooperative movement and organisations focused on consumption were highly important in the early years of the labour movement; these were often run by people with reformist and moderate positions.

By the late 19th century, Manlleu had six cooperatives, all of which dealt in consumer goods, and by 1901, they had 300 members. Their main activity involved the sale of groceries at an affordable price. In 1903, a group of workers from Dolcet founded the Mutual Bread Cooperative and were the first organisation of this kind to build a bakery. It was solely dedicated to the sale of bread, which was a staple food. It was a workers’ society, as only salaried employees could be members. By 1908, it too had 300 members. In 1909 it merged with three more cooperatives: the Alliance, the Family and the Future, which were also dedicated to food commerce, and it took on its definitive name: The Mutual Cooperative of Bread and Groceries. The body was a leading entity in Catalonia within the cooperative movement. It allocated part of its profits to a collective fund for health care, as well as to cultural and educational activities. It offered subsidies for disability and old age, medical assistance and support in the event of a death or job loss, in addition to nursery maintenance and the promotion of housing, it was very advanced for its time. In 1916 its main offices were built in the Plaça de Fra Bernadí, in the very heart of Manlleu. In 1936, the cooperative had 700 families registered as members.

74

Trade Unions

At the same time as these cultural and mutual aid organizations began to emerge, in which workers gathered to defend their interests, a forceful trade union movement was also gaining strength. This movement put forward new ideological proposals, and was closely linked to Republican, Socialist and Anarchist groups. The Catholic Church meanwhile also wielded influence with a new form of social Catholicism.

At first, trade union organisations were small, and local in nature, and they were disconnected from larger. In the early 1870s, small groups existed in several towns on the Ter that were linked to the national trade union Les Tres Classes de Vapor, which was mainly Socialist in its ideology. In 1870, Manlleu possessed one of the strongest branches of this union in Catalonia. Group members took part in the founding congress of the General Union of Workers (UGT). In 1900, the textile workers of Manlleu took part in a new attempt to reorganize trade unionism with the Spanish Textile Federation (FTE) in a move that lasted only a few years. The FTE set up its head offices in Manlleu, and appointed Josep Guiteras from Manlleu as the Secretary of the Central Committee. As early as the twentieth century, Socialist and Anarchist trade unionism was organized into different groups. From 1904 onwards, Socialism was grouped around the Workers’ Society of Manufacturing Art and Annexes of Manlleu, while anarchist trade union activities were organized within the Sole Workers’ Union of Manlleu.

75

The Manufacturer’s Association of Manlleu and Manlleu County

With the workers already organized and in response to growing social conflict, employers’ organizations were created in the late 19th century with the aim of countering some of the demands made by the workers’ associations. These bodies facilitated coordination with workers, while helping to resolve conflicts between the factory owners themselves. Manufacturers had also become class-conscious.

The Manufacturer’s Association of Manlleu and Manlleu County was founded in 1892, its head office was on la Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes in Barcelona. This association was backed by two of the most important textile manufacturers of the time, the cotton producers from the town, Albert Rusiñol and Vicenç Casacuberta, although most of the industrialists with factories in Manlleu, such as Almeda, Sanglas, Vilaseca and Comas also joined almost immediately. In 1899 it expanded its scope and became known as the Ter and Freser Manufacturers Association, and was also managed under the auspices of Albert Rusiñol, who was at the time the President of National Employer's Organisation. The association played a leading role during the period of conflicts at the end of the century as well as in the upheavals caused by the events of March 1901, when there were serious clashes between workers and law enforcement bodies. The association spoke out against the passing of a law that created mixed juries to resolve disputes between employers and workers.

76

The Weavers’ Association

This organisation was linked to the Vic Weavers’ Association. It was founded in 1841, with seventy-two members. It is the first known organizational manifestation of the Manlleu labour movement.

Catholic Youth

Founded in 1878. This cultural entity with Catholic roots has had a great deal of influence in Manlleu. From its very start it had both a café and a small theatre. In 1898 it had 150 members. It has survived to the present day.

77

Mount of Piety of the Manufacturing Union of Manlleu and Region

Founded in 1892, this was a mutual aid society for cases of illness. It also offered help to workers who had been laid-off. In 1898 it had 172 members, most of whom were heads of their respective sections. In 1902 it attempted to set up a production cooperative.

The Workers’ Society (Manlleu Workers)

Established in 1897. This body was housed on the ground floor of number 10 Carrer del Ter, in the same location as the former offices of the Progress Choral Society. It sought to provide healthcare aid for its partners in the event of illness, and to defend the interests of workers. In 1898 it had 400 members. It was also actively involved in various labour disputes.

78

The Rafael de Casanova Catalanist Association

Also known by its nickname Can Catalans. The organisation was founded in March 1899, although it may be considered to be a continuation of the Catalan Centre, which had stopped its activities a couple of years earlier. During the fifteen years of its existence it carried out numerous activities, including theatre trips and hiking.

The Harmony Cooperative

In 1901 a group of workers and craftsmen from Manlleu began preparations for the creation of the Harmony production cooperative. A year later, the textile factory on Carrer de la Cavalleria was already in operation. It shut down in 1911 following a crisis.

79

The Our Lady of Carmel Workers’ Association

Founded in 1888. This was a religious organisation that sought, not to promote a certain cause, but to prevent strikes and conflicts between factory owners and workers. It halted its activities in 1891.

Our Lady of Carmel was the patron saint of workers. Many entities in Manlleu accepted this patronage in their names, even some of those linked to the leftwing trade union of the Tres Classes de Vapor trade union organisation.

The Traditionalist Centre

Founded in 1890. This body was linked to the Traditionalist Party and brought together the Carlist group from Manlleu, it was mainly linked to rural landowners. It ceased functioning on 17 August 1898.

80

The Workers’ Society of Manufacturing Art and Annexes

Founded in 1904. This Manlleu-based socialist trade union sought to defend workers’ rights. It was associated with the national UGT trade union. It lasted until 1923.

The Catholic Workers Mutual Bread Cooperative. “The Catholics”

This body appeared in 1910, breaking away from the Mutual Bread Cooperative of Manlleu, in order to produce and sell bread. The split occurred as a reaction to the decision of the Mutual Bread Cooperative to allocate part of their profits to the creation of a collective capital to create new services for members.

The Sole Trade Union

Founded in 1922. This body sought to defend workers and create areas in which to educate them. This union was attached to the CNT national trade union body. It continued to operate until 1934.

81

The Star Choral Society

Founded in 1877. This organisation aimed to entertain and educate its associates, who were mostly workers. It owned both cafe and a library. It also organized theatrical performances, dancing and choirs at the Café Garcia. In 1898 it had 60 members.

82

A Dynamic Society

Industrialization affected all walks of life, even beyond the economic transformations it brought to the entire Ter basin. Despite the difficult living conditions of the workers and the conflicts, the new industrial society bore with it an unprecedented dynamism: the idea of a shared life rose to the fore. Interest in education, leisure, sport and culture was manifest with energy and in diverse manners. In the early the 20th century, the social world of Manlleu was the most diverse and sophisticated in the whole of the Bishopric of Vic. It was definitely a new society, urban to the full, and it was highly active.

83

The Inevitable Conflict

This society, which was created by industrialization, was highly prone to conflict. It was characterized by great social differences, by the precarious living conditions of the new working class, by a lack of political freedom and limits on free association, it bore witness to a confrontation of interests between manufacturers and workers, clashes between the religious and the anticlericals, not to mention industrial crises that shook the foundations of this new world.

84

Squirrels! - 1852

The industrial revolution involved the general use of strikes as a means to enforce the workers’ demands. In Manlleu one of the first strikes to have taken place in the Ter region has left its mark on the workers’ rights movement in Spain. In 1852 the factory owner, Sala decided to lower wages with respect to the production of certain clothing items. The response of the workers from Manlleu was to refuse to weave them. Faced with this situation, the manufacturer took the work that the people of Manlleu had refused to do, and assigned it to workers in the neighbouring village of Santa Maria de Corcó, which is otherwise known as L’Esquirol. Today strikebreakers in both in Catalan and Spanish are known as ‘esquirols’ – or in English, squirrels.

85

The Cotton Famine – 1862-1865

During the 19th century, the industrial workers, who were permanently isolated from the countryside, and who were dependent on their own commercial activities for food, were still highly exposed to the economic crises of the textile industry, which often quickly became food crises. This occurred during the cotton famine between 1862 and 1865. The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 severely affected cotton imports. The factories of the Ter were forced to minimise their production and many workers were fired. The manufacturing centres of the Ter suffered heavily. In Manlleu, the City Council organized community food drives to alleviate hunger problems and many families had to leave the industrial centres.

86

The Events of March 1901

The end of the 19th century was especially contentious as the result of an economic crisis and the loss of the Spanish colonies. Strikes grew throughout the entire region of the Ter basin. The manufacturers, members of the Association of Manufacturers of the Ter and the Freser, used what was called the hunger pact, to lay off the most problematic workers and deny them work in any of their factories. The situation was extremely tense and culminating moment came in March 1901. On 11 March, the manufacturers, who remained inflexible, implemented a coordinated lockout (factory closures) throughout the basin, which provoked the reaction of the workers from Ripoll to Roda de Ter. A worker in Torelló, Gaspar Vigué, and another in Ripoll, died in clashes with the police. The lockout lasted for a week, and those workers who had been fired were finally readmitted. The issue was even debated in the cabinet of the Spanish government.

87

Clericalism and Anticlericalism

The penetration of Republicanism, Anarchism and Socialism, secular and even anti-clerical ideologies led the Church to react, in coordination with the manufacturers. Josep Morgades and Josep Torras i Bages, the bishops of Vic between 1882 and 1916, and Francesc d’Assís Aguilar from Manlleu, the Bishop of Segorbe, led a new social Catholicism movement that sought to divert workers away from protests and revolutionary paths. One of the areas in which this confrontation took place was in education, a fact revealed in the conflicts over the secular school of the Progress Society. It opened during the 1880s, and finally closed its doors for ever in 1909, after the events of the Tragic Week. It had already been closed on several occasions, and the occasionally violent confrontations between its supporters and its detractors often altered coexistence in the town.

88

EPILOGUE

Industrialization is a historical process that has strongly defined the Catalonia of today. The Ter basin in general and Manlleu specifically, both experienced the transformation that came with rural societies that were moulded into forming a markedly industrial society. The Ter was the driving force of this change. This process has left us with an industrial culture that has been passed on to the present from generation to generation, and it is one that coexists with the rural soul of the Osona region.

Evaluating the worth of this industrial culture (in material and immaterial terms) involves an analysis of the entrepreneurial capacity and dynamism of both industrialists and their workers; the continued effort of both groups, not to mention women, an invisible majority; and the emergence of a highly active civil society and one with a great capacity for association.

Entrepreneurship, innovation, effort and cooperation are values that are still useful and intrinsic to our industrial culture. They are solid foundations that we need to preserve, and on which the future can be built.